Seeds Gallery Com,

5/

5

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" />

</head>

<body>

<h2><strong>Bourbon Vanilla Seeds (Vanilla planifolia)</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 50 or 100 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p><span>Vanilla planifolia is a species of vanilla orchid. It is native to Mexico and Central America, and is one of the primary sources for vanilla flavouring, due to its high vanillin content. Common names are flat-leaved vanilla, Tahitian vanilla,[citation needed] and West Indian vanilla (also used for the Pompona vanilla, V. pompona). Often, it is simply referred to as "the vanilla". It was first scientifically named in 1808.</span></p>

<p><span>Vanilla planifolia is found in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and northeastern South America. It prefers hot, wet, tropical climates. </span></p>

<p><span>It is cultivated and harvested primarily in Veracruz, Mexico and in Madagascar.</span></p>

<p><span>Like all members of the genus Vanilla, V. planifolia is a vine. It uses its fleshy roots to support itself as it grows.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Flowers</span></strong></p>

<p><span>Flowers are greenish-yellow, with a diameter of 5 cm (2 in). They last only a day, and must be pollinated manually, during the morning, if fruit is desired. The plants are self-fertile, and pollination simply requires a transfer of the pollen from the anther to the stigma. If pollination does not occur, the flower is dropped the next day. In the wild, there is less than 1% chance that the flowers will be pollinated, so in order to receive a steady flow of fruit, the flowers must be hand-pollinated when grown on farms.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Fruit</span></strong></p>

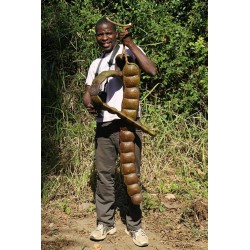

<p><span>Fruit is produced only on mature plants, which are generally over 3 m (10 ft) long. The fruits are 15-23 cm (6-9 in) long pods (often incorrectly called beans). Outwardly they resemble small bananas. They mature after about five months, at which point they are harvested and cured. Curing ferments and dries the pods while minimizing the loss of essential oils. Vanilla extract is obtained from this portion of the plant.</span></p>

<p><span>Vanilla is a flavoring derived from orchids of the genus Vanilla, primarily from the Mexican species, flat-leaved vanilla (V. planifolia). The word vanilla, derived from vainilla, the diminutive of the Spanish word vaina (vaina itself meaning sheath or pod), is translated simply as "little pod". Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican people cultivated the vine of the vanilla orchid, called tlilxochitl by the Aztecs. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés is credited with introducing both vanilla and chocolate to Europe in the 1520s.</span></p>

<p><span>Pollination is required to set the vanilla fruit from which the flavoring is derived. In 1837, Belgian botanist Charles François Antoine Morren discovered this fact and pioneered a method of artificially pollinating the plant.[3] The method proved financially unworkable and was not deployed commercially.[4] In 1841, Edmond Albius, a slave who lived on the French island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean, discovered at the age of 12 that the plant could be hand-pollinated. Hand-pollination allowed global cultivation of the plant.</span></p>

<p><span>Three major species of vanilla currently are grown globally, all of which derive from a species originally found in Mesoamerica, including parts of modern-day Mexico.[6] They are V. planifolia (syn. V. fragrans), grown on Madagascar, Réunion, and other tropical areas along the Indian Ocean; V. tahitensis, grown in the South Pacific; and V. pompona, found in the West Indies, and Central and South America.[7] The majority of the world's vanilla is the V. planifolia species, more commonly known as Bourbon vanilla (after the former name of Réunion, Île Bourbon) or Madagascar vanilla, which is produced in Madagascar and neighboring islands in the southwestern Indian Ocean, and in Indonesia.</span></p>

<p><span>Vanilla is the second-most expensive spice after saffron. Despite the expense, vanilla is highly valued for its flavor. As a result, vanilla is widely used in both commercial and domestic baking, perfume manufacture, and aromatherapy.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>History</span></strong></p>

<p><span>According to popular belief, the Totonac people, who inhabit the east coast of Mexico in the present-day state of Veracruz, were the first to cultivate vanilla. According to Totonac mythology, the tropical orchid was born when Princess Xanat, forbidden by her father from marrying a mortal, fled to the forest with her lover. The lovers were captured and beheaded. Where their blood touched the ground, the vine of the tropical orchid grew.[4] In the 15th century, Aztecs invading from the central highlands of Mexico conquered the Totonacs, and soon developed a taste for the vanilla pods. They named the fruit tlilxochitl, or "black flower", after the matured fruit, which shrivels and turns black shortly after it is picked. Subjugated by the Aztecs, the Totonacs paid tribute by sending vanilla fruit to the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan.</span></p>

<p><span>Until the mid-19th century, Mexico was the chief producer of vanilla. In 1819, French entrepreneurs shipped vanilla fruits to the islands of Réunion and Mauritius in hopes of producing vanilla there. After Edmond Albius discovered how to pollinate the flowers quickly by hand, the pods began to thrive. Soon, the tropical orchids were sent from Réunion to the Comoros Islands, Seychelles, and Madagascar, along with instructions for pollinating them. By 1898, Madagascar, Réunion, and the Comoros Islands produced 200 metric tons of vanilla beans, about 80% of world production. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, Indonesia is currently responsible for the vast majority of the world's Bourbon vanilla production and 58% of the world total vanilla fruit production.</span></p>

<p><span>The market price of vanilla rose dramatically in the late 1970s after a tropical cyclone ravaged key croplands. Prices remained high through the early 1980s despite the introduction of Indonesian vanilla. In the mid-1980s, the cartel that had controlled vanilla prices and distribution since its creation in 1930 disbanded. Prices dropped 70% over the next few years, to nearly US$20 per kilogram; prices rose sharply again after tropical cyclone Hudah struck Madagascar in April 2000. The cyclone, political instability, and poor weather in the third year drove vanilla prices to an astonishing US$500/kg in 2004, bringing new countries into the vanilla industry. A good crop, coupled with decreased demand caused by the production of imitation vanilla, pushed the market price down to the $40/kg range in the middle of 2005. By 2010, prices were down to $20/kg. Cyclone Enawo caused in similar spike to $500/kg in 2017.</span></p>

<p><span>Madagascar (especially the fertile Sava region) accounts for much of the global production of vanilla. Mexico, once the leading producer of natural vanilla with an annual yield of 500 tons of cured beans, produced only 10 tons in 2006. An estimated 95% of "vanilla" products are artificially flavored with vanillin derived from lignin instead of vanilla fruits.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Etymology</span></strong></p>

<p><span>Vanilla was completely unknown in the Old World before Cortés. Spanish explorers arriving on the Gulf Coast of Mexico in the early 16th century gave vanilla its current name. Spanish and Portuguese sailors and explorers brought vanilla into Africa and Asia later that century. They called it vainilla, or "little pod". The word vanilla entered the English language in 1754, when the botanist Philip Miller wrote about the genus in his Gardener’s Dictionary. Vainilla is from the diminutive of vaina, from the Latin vagina (sheath) to describe the shape of the pods.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Vanilla orchid</span></strong></p>

<p><span>The main species harvested for vanilla is V. planifolia. Although it is native to Mexico, it is now widely grown throughout the tropics. Indonesia and Madagascar are the world's largest producers. Additional sources include V. pompona and V. tahitiensis (grown in Niue and Tahiti), although the vanillin content of these species is much less than V. planifolia.</span></p>

<p><span>Vanilla grows as a vine, climbing up an existing tree (also called a tutor), pole, or other support. It can be grown in a wood (on trees), in a plantation (on trees or poles), or in a "shader", in increasing orders of productivity. Its growth environment is referred to as its terroir, and includes not only the adjacent plants, but also the climate, geography, and local geology. Left alone, it will grow as high as possible on the support, with few flowers. Every year, growers fold the higher parts of the plant downward so the plant stays at heights accessible by a standing human. This also greatly stimulates flowering.</span></p>

<p><span>The distinctively flavored compounds are found in the fruit, which results from the pollination of the flower. These seed pods are roughly a third of an inch by six inches, and brownish red to black when ripe. Inside of these pods is an oily liquid full of tiny seeds.[22] One flower produces one fruit. V. planifolia flowers are hermaphroditic: they carry both male (anther) and female (stigma) organs. However, self-pollination is blocked by a membrane which separates those organs. The flowers can be naturally pollinated by bees of genus Melipona (abeja de monte or mountain bee), by bee genus Eulaema, or by hummingbirds. The Melipona bee provided Mexico with a 300-year-long advantage on vanilla production from the time it was first discovered by Europeans. The first vanilla orchid to flower in Europe was in the London collection of the Honourable Charles Greville in 1806. Cuttings from that plant went to Netherlands and Paris, from which the French first transplanted the vines to their overseas colonies. The vines grew, but would not fruit outside Mexico. Growers tried to bring this bee into other growing locales, to no avail. The only way to produce fruits without the bees is artificial pollination. Today, even in Mexico, hand pollination is used extensively.</span></p>

<p><span>In 1836, botanist Charles François Antoine Morren was drinking coffee on a patio in Papantla (in Veracruz, Mexico) and noticed black bees flying around the vanilla flowers next to his table. He watched their actions closely as they would land and work their way under a flap inside the flower, transferring pollen in the process. Within hours, the flowers closed and several days later, Morren noticed vanilla pods beginning to form. Morren immediately began experimenting with hand pollination. A few years later in 1841, a simple and efficient artificial hand-pollination method was developed by a 12-year-old slave named Edmond Albius on Réunion, a method still used today. Using a beveled sliver of bamboo, an agricultural worker lifts the membrane separating the anther and the stigma, then, using the thumb, transfers the pollinia from the anther to the stigma. The flower, self-pollinated, will then produce a fruit. The vanilla flower lasts about one day, sometimes less, so growers have to inspect their plantations every day for open flowers, a labor-intensive task.</span></p>

<p><span>The fruit, a seed capsule, if left on the plant, ripens and opens at the end; as it dries, the phenolic compounds crystallize, giving the fruits a diamond-dusted appearance, which the French call givre (hoarfrost). It then releases the distinctive vanilla smell. The fruit contains tiny, black seeds. In dishes prepared with whole natural vanilla, these seeds are recognizable as black specks. Both the pod and the seeds are used in cooking.</span></p>

<p><span>Like other orchids' seeds, vanilla seeds will not germinate without the presence of certain mycorrhizal fungi. Instead, growers reproduce the plant by cutting: they remove sections of the vine with six or more leaf nodes, a root opposite each leaf. The two lower leaves are removed, and this area is buried in loose soil at the base of a support. The remaining upper roots cling to the support, and often grow down into the soil. Growth is rapid under good conditions.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Cultivars</span></strong></p>

<p><strong><span>Bourbon vanilla</span></strong><span> or Bourbon-Madagascar vanilla, produced from V. planifolia plants introduced from the Americas, is from Indian Ocean islands such as Madagascar, the Comoros, and Réunion, formerly the Île Bourbon. It is also used to describe the distinctive vanilla flavor derived from V. planifolia grown successfully in tropical countries such as India.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Mexican vanilla</span></strong><span>, made from the native V. planifolia,[26] is produced in much less quantity and marketed as the vanilla from the land of its origin. Vanilla sold in tourist markets around Mexico is sometimes not actual vanilla extract, but is mixed with an extract of the tonka bean, which contains the toxin coumarin. Tonka bean extract smells and tastes like vanilla, but coumarin has been shown to cause liver damage in lab animals and has been banned in food in the US by the Food and Drug Administration since 1954.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Tahitian vanilla</span></strong><span> is from French Polynesia, made with V. tahitiensis. Genetic analysis shows this species is possibly a cultivar from a hybrid of V. planifolia and V. odorata. The species was introduced by French Admiral François Alphonse Hamelin to French Polynesia from the Philippines, where it was introduced from Guatemala by the Manila Galleon trade.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>West Indian vanilla</span></strong><span> is made from V. pompona grown in the Caribbean and Central and South America.</span></p>

<p><span>The term French vanilla is often used to designate particular preparations with a strong vanilla aroma, containing vanilla grains and sometimes also containing eggs (especially egg yolks). The appellation originates from the French style of making vanilla ice cream with a custard base, using vanilla pods, cream, and egg yolks. Inclusion of vanilla varietals from any of the former French dependencies or overseas France may be a part of the flavoring. Alternatively, French vanilla is taken to refer to a vanilla-custard flavor.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Chemistry</span></strong></p>

<p><span>Vanilla essence occurs in two forms. Real seedpod extract is a complex mixture of several hundred different compounds, including vanillin, acetaldehyde, acetic acid, furfural, hexanoic acid, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, eugenol, methyl cinnamate, and isobutyric acid.[citation needed] Synthetic essence consists of a solution of synthetic vanillin in ethanol. The chemical compound vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde) is a major contributor to the characteristic flavor and aroma of real vanilla and is the main flavor component of cured vanilla beans.[30] Vanillin was first isolated from vanilla pods by Gobley in 1858. By 1874, it had been obtained from glycosides of pine tree sap, temporarily causing a depression in the natural vanilla industry. Vanillin can be easily synthesized from various raw materials, but the majority of food-grade (> 99% pure) vanillin is made from guaiacol.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Pollination</span></strong></p>

<p><span>Flowering normally occurs every spring, and without pollination, the blossom wilts and falls, and no vanilla bean can grow. Each flower must be hand-pollinated within 12 hours of opening. In the wild, very few natural pollinators exist, with most pollination thought to be carried out by the shiny green Euglossa viridissima, some Eulaema spp. and other species of the euglossine or orchid bees, Euglossini, though direct evidence is lacking. Closely related Vanilla species are known to be pollinated by the euglossine bees.[40] The previously suggested pollination by stingless bees of the genus Melipona is thought to be improbable, as they are too small to be effective and have never been observed carrying Vanilla pollen or pollinating other orchids, though they do visit the flowers.[41] These pollinators do not exist outside the orchid's home range, and even within that range, vanilla orchids have only a 1% chance of successful pollination. As a result, all vanilla grown today is pollinated by hand. A small splinter of wood or a grass stem is used to lift the rostellum or move the flap upward, so the overhanging anther can be pressed against the stigma and self-pollinate the vine. Generally, one flower per raceme opens per day, so the raceme may be in flower for over 20 days. A healthy vine should produce about 50 to 100 beans per year, but growers are careful to pollinate only five or six flowers from the 20 on each raceme. The first flowers that open per vine should be pollinated, so the beans are similar in age. These agronomic practices facilitate harvest and increases bean quality. The fruits require five to six weeks to develop, but around six months to mature. Over-pollination results in diseases and inferior bean quality.[35] A vine remains productive between 12 and 14 years.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Harvest</span></strong></p>

<p><span>Harvesting vanilla fruits is as labor-intensive as pollinating the blossoms. Immature, dark green pods are not harvested. Pale yellow discoloration that commences at the distal end of the fruits is not a good indication of the maturity of pods. Each fruit ripens at its own time, requiring a daily harvest. "Current methods for determining the maturity of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) beans are unreliable. Yellowing at the blossom end, the current index, occurs before beans accumulate maximum glucovanillin concentrations. Beans left on the vine until they turn brown have higher glucovanillin concentrations but may split and have low quality. Judging bean maturity is difficult as they reach full size soon after pollination. Glucovanillin accumulates from 20 weeks, maximum about 40 weeks after pollination. Mature green beans have 20% dry matter but less than 2% glucovanillin."[46] The accumulation of dry matter and glucovanillin are highly correlated.To ensure the finest flavor from every fruit, each individual pod must be picked by hand just as it begins to split on the end. Overmatured fruits are likely to split, causing a reduction in market value. Its commercial value is fixed based on the length and appearance of the pod.</span></p>

<p><span>If the fruit is more than 15 cm (5.9 in) in length, it is categorized as first-quality. The largest fruits greater than 16 cm and up to as much as 21 cm are usually reserved for the gourmet vanilla market, for sale to top chefs and restaurants. If the fruits are between 10 and 15 cm long, pods are under the second-quality category, and fruits less than 10 cm in length are under the third-quality category. Each fruit contains thousands of tiny black vanilla seeds. Vanilla fruit yield depends on the care and management given to the hanging and fruiting vines. Any practice directed to stimulate aerial root production has a direct effect on vine productivity. A five-year-old vine can produce between 1.5 and 3 kg (3.3 and 6.6 lb) pods, and this production can increase up to 6 kg (13 lb) after a few years. The harvested green fruit can be commercialized as such or cured to get a better market price.</span></p>

<p><strong><span>Culinary uses</span></strong></p>

<p><span>The four main commercial preparations of natural vanilla are:</span></p>

<p><span>Whole pod</span></p>

<p><span>Powder (ground pods, kept pure or blended with sugar, starch, or other ingredients)</span></p>

<p><span>Extract (in alcoholic or occasionally glycerol solution; both pure and imitation forms of vanilla contain at least 35% alcohol)</span></p>

<p><span>Vanilla sugar, a packaged mix of sugar and vanilla extract</span></p>

<p><span>Vanilla flavoring in food may be achieved by adding vanilla extract or by cooking vanilla pods in the liquid preparation. A stronger aroma may be attained if the pods are split in two, exposing more of a pod's surface area to the liquid. In this case, the pods' seeds are mixed into the preparation. Natural vanilla gives a brown or yellow color to preparations, depending on the concentration. Good-quality vanilla has a strong, aromatic flavor, but food with small amounts of low-quality vanilla or artificial vanilla-like flavorings are far more common, since true vanilla is much more expensive.</span></p>

<p><span>Regarded as the world's most popular aroma and flavor, vanilla is a widely used aroma and flavor compound for foods, beverages and cosmetics, as indicated by its popularity as an ice cream flavor.[64] Although vanilla is a prized flavoring agent on its own, it is also used to enhance the flavor of other substances, to which its own flavor is often complementary, such as chocolate, custard, caramel, coffee, and others. Vanilla is a common ingredient in Western sweet baked goods, such as cookies and cakes.</span></p>

<p><span>The food industry uses methyl and ethyl vanillin as less-expensive substitutes for real vanilla. Ethyl vanillin is more expensive, but has a stronger note. Cook's Illustrated ran several taste tests pitting vanilla against vanillin in baked goods and other applications, and to the consternation of the magazine editors, tasters could not differentiate the flavor of vanillin from vanilla; however, for the case of vanilla ice cream, natural vanilla won out.[66] A more recent and thorough test by the same group produced a more interesting variety of results; namely, high-quality artificial vanilla flavoring is best for cookies, while high-quality real vanilla is slightly better for cakes and significantly better for unheated or lightly heated foods. The liquid extracted from vanilla pods was once believed to have medical properties, helping with various stomach ailments.</span></p>

</body>

</html>

MHS 104